Reconciling painful past may create hope

The Western Producer recognizes this year’s National Day of Truth and Reconciliation with a package of stories and opinion pieces about past injustices and steps that are being taken for a brighter future. The other stories in this package are linked below.

More than a century after its creation, no visible sign remains of the File Hills farm colony in southern Saskatchewan.

But the pain caused through an experiment that epitomized the culture of assimilation in that era’s attitudes toward Canada’s Indigenous peoples still lives in the collective memories of residential school survivors.

Now a new generation, this time under Indigenous leadership, is working to create a different future for First Nations in the agricultural sector.

Other stories in our Truth and Reconciliation feature:

Thomas Benjoe, president and chief executive officer of FHQ Developments, says the File Hills Colony is an example of how projects once touted as progressive held back Indigenous agriculture.

He is leading First Nations efforts in the File Hills area to carve out a new history. FHQ Developments is operated by the 11 First Nations, including Peepeekisis, that belong to the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council.

The history

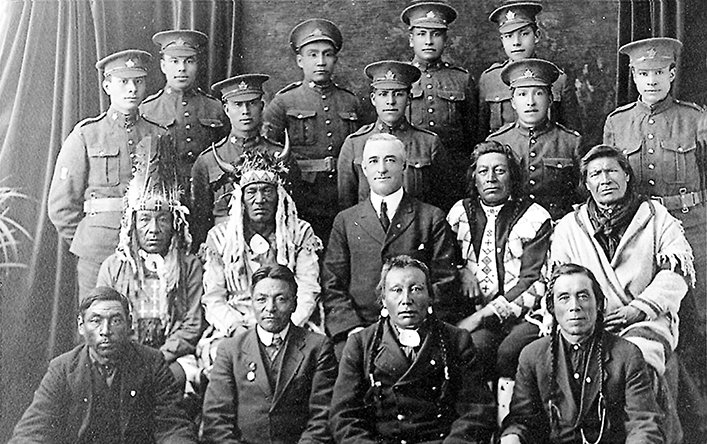

As the 19th century bled into the 20th, regional Indian Agent William Morris Graham devised the File Hills colony as a way to prevent Indigenous residential school graduates from reverting to traditional lifestyles.

Specially chosen graduates of residential schools were given an opportunity to farm on prime agriculture land belonging to the Peepeekisis Cree Nation, even though many were not members of that nation.

Members of Peepeekisis were displaced to a smaller area, while select graduates were encouraged to live like colonial homesteaders and were afforded many luxuries their peers didn’t have.

The Canadian government saw the colony as an example of how Indigenous populations could be assimilated but disregarded the way it prevented other First Nations from acquiring land, machinery and capital.

Indigenous farmers were at the mercy of Indian Agents who could limit what was grown and control access to equipment and land.

The File Hills Colony was riddled with controversy after disputes over redistribution of reserve lands and suspicion that government agents were reaping some of the profits.

Legal action was filed in the 1950s to have the colony removed.

Compensation

Earlier this year, the federal government provided $150 million in compensation to Peepeekisis First Nation, with an option to acquire 18,720 acres of land.

“In creating and implementing the Colony Scheme, Canada breached its fiduciary duty to the Nation by failing to protect the Nation’s interest in the land and not providing any compensation to the Nation,” says a government release.

“The historic and ongoing harm that the Colony Scheme caused to the Peepeekisis Nation created community divisions and animosity between families and members. The legacy of the Colony Scheme continues to impact the Nation to this day.”

Now considered an oppressive example of colonial power, the colony at File Hills illustrated Canadian government efforts to force a Euro-centric, agrarian way of life upon Indigenous communities.

“All of these things, all of these policies, have significantly worked against Indigenous communities to be able to actively participate and create that long history of what we need in the ag industry,” says Benjoe.

Overcoming that history and re-engaging in agriculture are important opportunities for First Nations, he added.

“It’s not just from a producer’s perspective, it’s from a tech, manufacturing and supply chain, where we’re looking at it in a much bigger picture of how we can invest in and how we can participate,” Benjoe says.

“We need to be a part of that leading edge work that is happening all around us, and if we don’t, we’re going to miss out on huge opportunities to participate and create and be a part of an industry that is both sustainable and renewable.”

Barriers remain

While the potential is real, so are the barriers.

Benjoe says the legacy of File Hills colony and other government policies led to “barriers for success” and reduced enthusiasm among First Nations for agricultural projects.

However, access to capital is the biggest hurdle.

“We just can’t compete in an agriculture industry that requires significant capital investment where we can’t get loans,” he says. “We just don’t have the access to capital that is required to be able to participate at the level that is needed in the ag industry.”

FHQ Developments is now looking elsewhere, away from reserves.

“We’re shifting as an organization towards those types of opportunities. Just because, you know, access to capital on reserve is going to be very, very difficult.”

It also seeks ways to establish collateral by finding low-risk entry points, says Benjoe.

“Over time, we’re able to demonstrate our capacity and be able to fully participate in much larger contracts and take on more risk with our customers. And so that’s what we need to see in the ag industry.”

Through the Saskatchewan Chamber of Commerce, Benjoe is trying to make it easier for companies inside and outside of agriculture to engage with First Nations through the creation of an Indigenous engagement charter.

“There’s no excuse for any organization, any business in Saskatchewan, to not do something. There’s resources, there’s tools, there’s training, there’s guidance. That’s all there for you now,” he says.

“You have all the levers to be able to allow us access. And if you don’t know how, or if you’re uncomfortable about going down this path, talk to us.”

There is a blueprint for engagement with First Nations. Benjoe points to the oil, gas and mining sectors as industries that established a foundation of active participation with Indigenous communities.

In those sectors, First Nation-specific procurement policies, engagement and community investment are more common than what is found in agriculture.

“What I need to be able to see and be able to advocate for is to work with those major ag companies and say, ‘Well, how can we get you thinking about reconciliation? How do we get the organization developing the right policies and making the right investments in unity?” he says.

“That’s where we see the opportunity, and that is why we are pushing forward within the ag industry.”

Champions sought

As Benjoe seeks “champions to step up” on the industry side of agriculture, he also expects more action from government.

“The role that government needs to play is around the policy and around the investment. We need them to make capital available or set up loan loss provisions for us,” he says.

Government programming specific to First Nations and agriculture has increased in recent years, but Benjoe says it is not sufficient.

The five-year, $8.5 million Indigenous Agriculture and Food Systems Initiative, launched by the federal government in 2018, is oversubscribed. The program was designed to “support Indigenous communities and entrepreneurs who are ready to launch agriculture and food systems projects and others who want to build their capacity to participate in the Canadian agriculture and agri-food sector.”

Funding per project was capped at $500,000 per year, and in 2021 – three years into the five-year mandate – applications were suspended because demand was too high.

“Indigenous communities want to participate. It’s just, you’re not putting enough effort and enough dollars towards it, that we can participate at a larger level,” Benjoe says.

“When I think about things that I want to participate in, in the ag tech or manufacturing or supply chain sector, there is a significant amount of capital that we’re going to have to invest.”

When Benjoe compares the limited funding available for Indigenous farming initiatives to the money spent to support farmers over the past century, he sees glaring inequities.

“There (is) all sort of programs set up, but there is nothing, there has never been anything really specific for Indigenous participation,” he says.

“There is a lot of catching up to do. Let’s just play a bit of catch up here and make sure that there’s good recurring programs that our communities can access and leverage into the investments and in the ag sector, and, you know, allow us to participate at a much higher level.”

The File Hills compensation package and other successful land claims don’t erase the impact of lost opportunities to develop agricultural enterprise and expertise, he says.

“We can’t just say agriculture is happening all around us and Indigenous people should just participate. We go back into that history and it was pretty restrictive for us to participate at the start.”

His concerns are echoed by the report from a parliamentary committee investigation into the state of Indigenous agriculture in Canada.

Jamie Hall, general manager of the Indian Agricultural Program of Ontario, says Indigenous farmers still face crippling restrictions in their access to capital.

“The Indian Act prevents individuals residing on reserve from pledging their assets as security, whether it be land, equipment or whatever else. That is an incredible roadblock to wealth creation and financing.

“The farm industry has expanded in Canada based on acceleration of land values and being able to borrow against that and leverage it for further growth. That opportunity does not exist among First Nations in First Nations communities,” Hall testified.

Testimony to the committee by the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association noted that Indigenous entrepreneurs who live off the reserve still have trouble obtaining financing because of low financial literacy rates, lack of credit history, lower home ownership rates and lower average net home values than the general population.

“The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada, in partnership with Indigenous communities, ensure that Indigenous financial institutions have the resources they need to operate and make the current funding conditions more flexible to promote Indigenous entrepreneurship in the agriculture and agri-food industry,” the committee said in its summary report.

Parliamentary Committee Recommendations

After hearing testimony from dozens of experts, a parliamentary study of Indigenous agriculture in Canada produced five recommendations in 2019:

• Recognize in government policies and programs the role that traditional and local food supply play in supporting the health of Indigenous communities, as well as the traditional importance of the land and agriculture for Indigenous communities.

• Ensure Indigenous financial institutions have resources to operate and make funding conditions more flexible to promote Indigenous entrepre- neurship in the industry.

• Consult Indigenous communities to assess how better financial support can be provided in the industry.

• Develop collaborative approaches to food and nutrition policy development with direct consultation and participation of Indigenous peoples.

• Make sure Indigenous communities are aware of supports for exports available to Canadian small businesses so they can take full benefit of them.

The federal government has not yet responded to the recommendations.

Source: producer.com