Higher cost of living demands competent governments

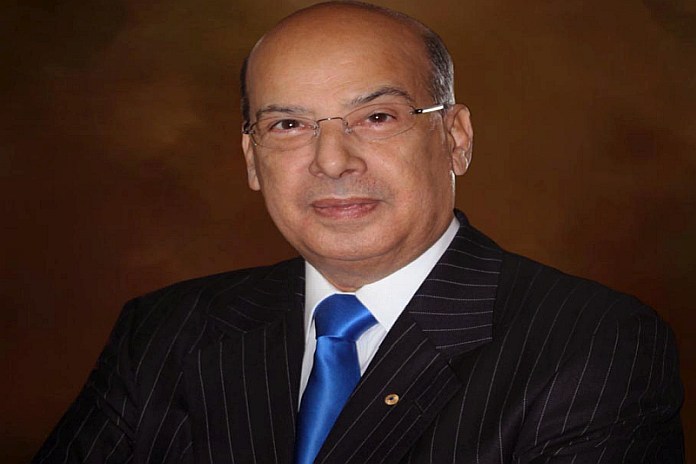

By Sir Ronald Sanders

Throughout the world, people and their governments and central banks are worrying about inflation, or the rate of increase in the cost of living. In many countries, this concern about the cost of living has become a prime consideration in general elections because electorates want competent governments in whose hands they commit their expectations.

Two questions arise: what is responsible for the cost of living, and can governments in small, developing countries, such as those in the Caribbean, take actions that would address the issue satisfactorily?

In the mid-term elections in the United States of America (US) last month, inflation (roughly translated as ‘the Economy’) was an issue that surfaced in early campaigning, although it waned toward the end. The main concern in the US was the high cost of oil that followed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the consequent efforts in Europe and North America to boycott Russian oil, or at least to minimize dependence on it.

The refusal of the big oil-producing countries to increase their output to compensate for shortages created by the isolation of Russia, increased oil prices globally. In turn, this caused the Biden administration in the US to release oil supplies from its strategic stock, reducing gasoline and diesel prices. Because of Biden’s action, by the time the mid-term elections were held, the value of this issue, in political terms, dropped to 38 percent amongst the electorate.

However, the oil issue persisted in Europe which had developed a dependence on Russian oil and gas. Europe will barely manage to keep prices down this winter only because European nations will utilize Russian supplies that they had stockpiled prior to the Russian war on Ukraine.

Both for the US and Europe, heating and its attendant costs to consumers will be a problem this winter. But next year will be worse if the isolation of Russian oil and gas from the world market continues. Stocks will be depleted if not exhausted, causing prices to soar.

All this could cause serious social unrest in Europe. There have already been protests in Greece, Belgium, Germany, France, Spain, Austria and the Czech Republic – the latter of which has seen household energy bills surge tenfold.

The world is also still experiencing the residual impact of the COVID-19 pandemic that severely disrupted supply chains for food, medicines, and commodities for construction and agriculture. Costs of construction materials increased by as much as 90 percent since the start of the pandemic.

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries, particularly the six smaller nations that comprise the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), have little control over the cost of living being experienced in their respective countries. As the Governor of the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB), Timothy Antoine, put it in July, “We import inflation, principally from the US and also from Europe our major trading partners”.

In the specific case of The Bahamas, largely because of geographic proximity, it conducts 85 percent of its trade with the US, importing almost $3 billion in goods in 2021 and giving the US a balance of trade surplus of $2.5 billion. Therefore, The Bahamas is very vulnerable to the impact of inflation in the US.

As small states, with limited capacity for the production of goods, Caribbean countries import from the US and Europe, bringing to their shores the high costs in those countries. Belize, Guyana and Suriname have some capacity to dull the impact of importing agricultural products because they are less reliant on such imports due to their relatively larger agricultural sectors. But even these three states still confront both the shortages and high prices for agricultural inputs, such as urea and ammonia.

In a sentence, the current rise in the cost of living is not due to policies of Caribbean governments; it is caused by external factors beyond the control of governments.

To be fair, all Caribbean governments, to one extent or another, have taken steps to cushion the effects of inflation on their populations, especially the poor and vulnerable. Many governments have introduced measures to subsidise the prices of basic foods. In the case of Antigua and Barbuda and Saint Lucia, for instance, the governments subsidise the costs of oil and gas. Furthermore, in Antigua and Barbuda, the government has written off arrears owed for electricity, water and property taxes, as further measures to ease the impact of imported inflation on the population.

A major consequence of these actions is that government revenues are diminishing, and their ability to service the demands of every sector of their society is considerably strained.

As is presently happening in Antigua and Barbuda and in Guyana, Caribbean governments will also have to increase wages and salaries, including the minimum wage, so that the general population can cope with increased prices. Overall, this will lead to higher per capita incomes, resulting in disqualification by international financial institutions from access to low-cost borrowing, precisely when Caribbean countries need it most.

In Antigua and Barbuda, the government and the private sector managed to agree on an increased minimum wage, recognizing that cost of living increases had to be met to maintain social and economic stability.

The big question that remains for the region is: when will the global economic disruption caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and consequent retaliation by the US, Canada and the European Union end? Right now, it looks set to drag on into next year.

Caribbean countries, therefore, should be working feverishly to implement the many plans, which they have agreed to increase trade in goods and services among themselves; to establish joint ventures for manufacturing and agricultural production; and for air and sea transportation. They also have to enhance the Caribbean Development Bank and consider new ways of investing Caribbean savings and profits by investing them within the region, rather than abroad.

In other words, the Caribbean has to become more self-sufficient and less vulnerable to external factors.

Source: caribbeannewsglobal.com