Smarter bug farming proves possible

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly used in farming, where they’re seen as innovative tools that can help farmers improve production, reduce labour and make better decisions faster.

Read Also

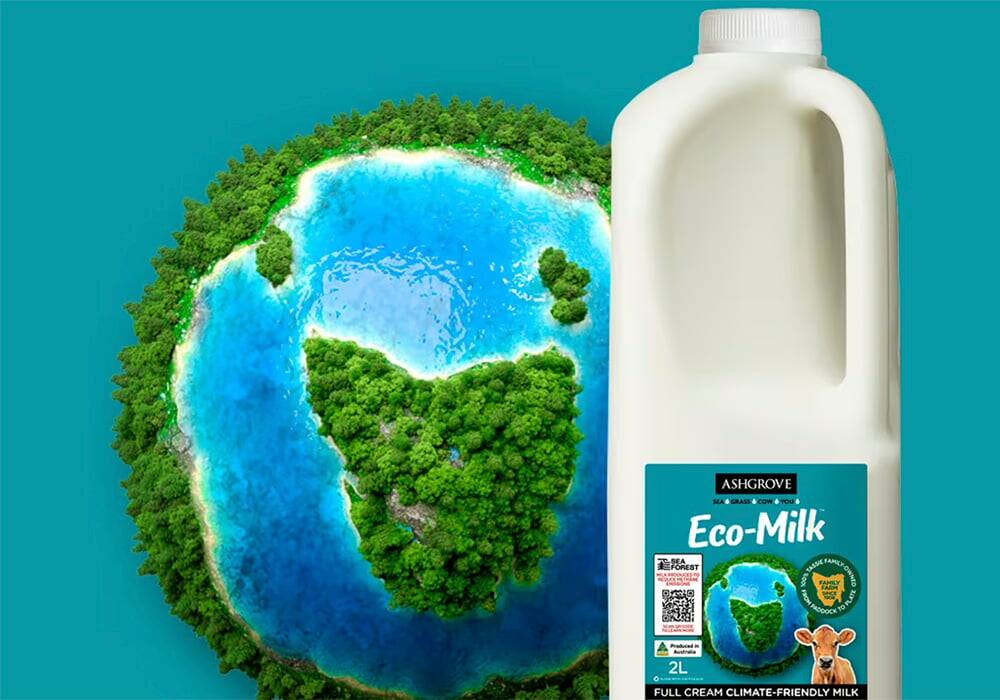

Thirst for ‘climate- friendly’ Ecomilk tested

A small dairy in the Australian state of Tasmania is stocking supermarket shelves with what it says is the world’s first branded milk produced by cows fed with a seaweed that makes them emit lower levels of environmentally damaging methane gas.

Natalie Duncan is taking it one step further. She’s bringing these applications to a new sector of agriculture — insect farming — with her start-up company Bug Mars and its Hexapod AI software.

Why it matters: Insect farmers face the same challenges with labour, productivity and disease that farmers of more conventional livestock do. It’s still an emerging sector in North America, so not many tools are available to address these issues.

“The highest cost in insect production is manual labour, especially around monitoring. It’s a brutal job crawling around insects to identify what’s wrong with them, so we are providing a tech solution for insect farms,” says Duncan, who is Bug Mars CEO and co-founder.

“Usually, people don’t want to hear of technology replacing people, but people like to be replaced here.”

Hexapod uses camera and sensor data gathered inside an insect production facility to analyze insect performance and offer yield predictions, notifications of temperature fluctuations and alerts of changes in bug behaviour that could signal the presence of disease.

According to Duncan, the system is a machine learning engine that makes smart decisions generated from the data it collects — and it learns based on data provided by Duncan and her team, which includes an entomologist and researchers from Carleton University and the United States Department of Agriculture.

Duncan’s experience growing crickets, and a connection with her co-founder Seth Hardy through another startup, ultimately led to development of Bug Mars and its technology for insect farmers.

“I was insect farming as a hobbyist and when I lost my job in arts during the pandemic, I wanted to scale my farm and sell the bugs — and the farm collapsed four times,” she recalls.

“Bugs are sensitive to light, sound, temperature and vibration, and I was sleeping in my office with the bugs trying to keep an eye on them. There are a lot of issues in scaling production. The more bugs you have, the more oversight you need to watch their behaviour and monitor their environment.”

Bug Mars is now working with 12 insect farms that are at various stages of increasing production, and the company hopes to sign its first paying customers later this month. A pivot in early 2024 from on-site to cloud-hosted machine learning has attracted interest from insect farmers in North America and as far away as Guatemala, Finland and Thailand.

Hexapod has models for crickets and black soldier flies and may expand into fruit flies and meal worms, depending on customer demand and market trends. The system can work for any size of farm, is fully scalable and integrates with virtually any camera and sensor with a customized API key provided by Bug Mars.

So far, the company has raised approximately $650,000 in grant funding, and hopes to launch an investment seed round this fall. It has also been part of the MaRS RBC Women in Cleantech Accelerator and the latest cohort of the Cultivator Agtech Accelerator program in Saskatchewan.

Saskatoon has just become home to the new North American Insect Centre, which opened July 31 and will focus on improving and optimizing insect production in Canada and the United States. Most edible insect production in North America is for pet food and livestock feed, including aquaculture.

Long term, Duncan says she is encouraged by its potential to replace soy as a protein source for livestock.

“Our vision for Bug Mars is making insects cost competitive (as a protein source). Ultimately, livestock producers care about bottom line, and we will have more animals (in the world) to feed ourselves,” she says.

“If you don’t want to eat bugs, you don’t have to, but if you want to keep eating meat, you should care about bugs.”

Source: Farmtario.com