Wilmot Orchard preserved for a millennium

Charles Stevens’ succession planning extends beyond who will take over the farm to protecting his Class 1 prime farmland for a millennium.

“I’m very proud,” he said during a ceremony on May 31, marking the family’s partnership with Ontario Farmland Trust. “I am the happiest man in the world.”

In 2022, he connected with Martin Straathof, Ontario Farmland Trust’s executive director, to investigate the two-year process of placing his Clarington, Ont. farm in a 999-year easement, which would designate the land as agricultural use only.

Read Also

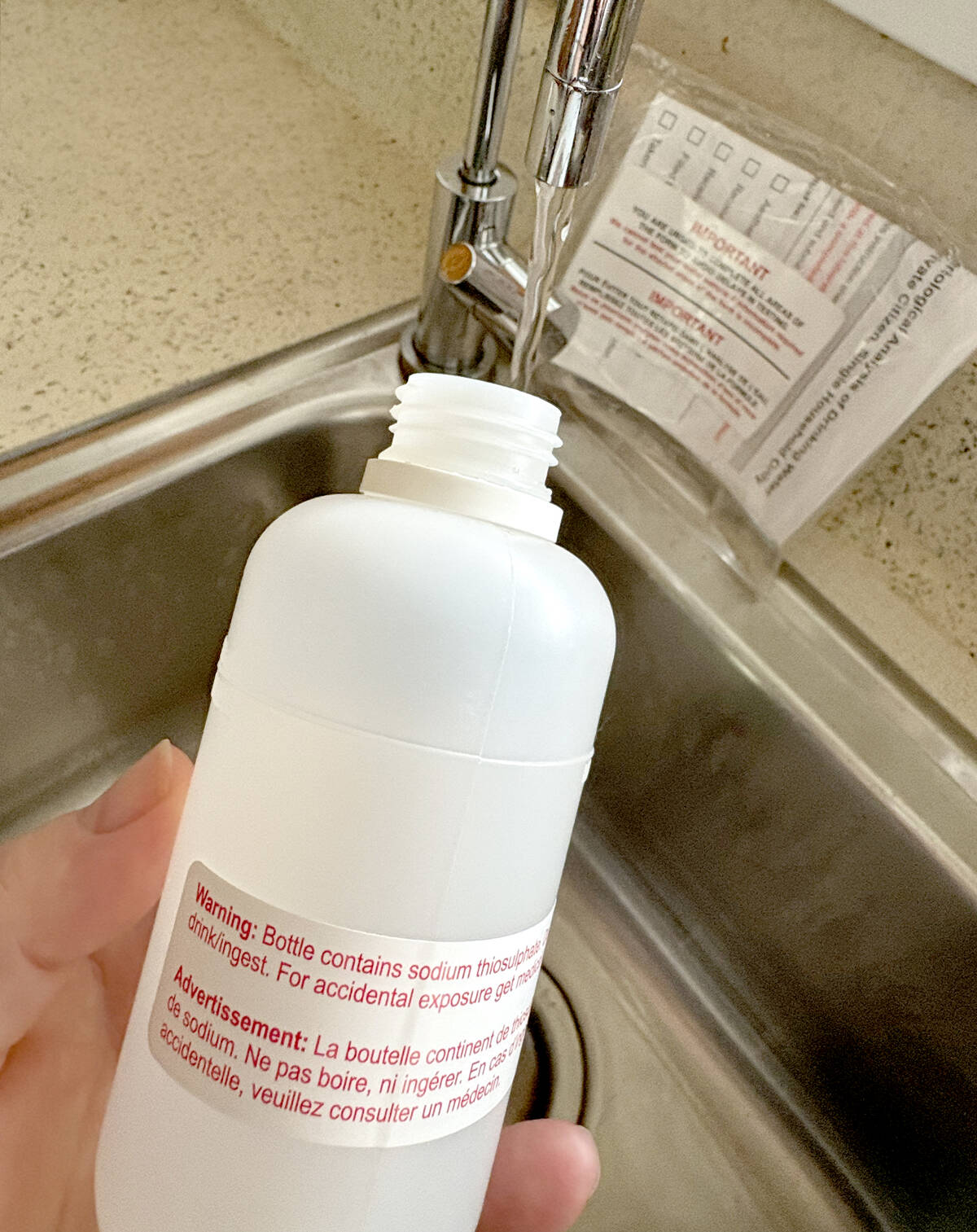

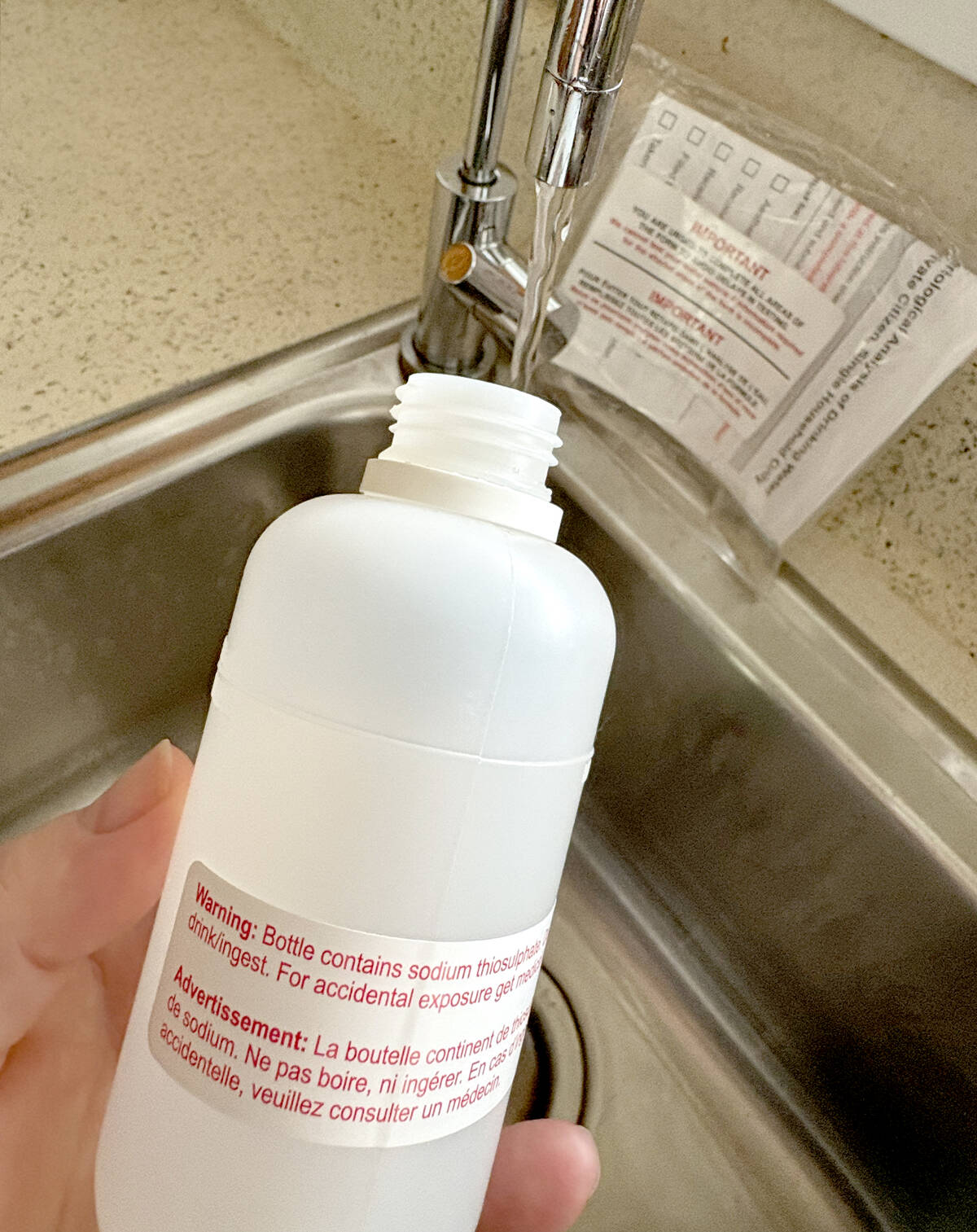

Walkerton water crisis ignited collaborative effort to protect water in Ontario

One of the most significant pieces of legislation instituted as a result of the Walkerton water crisis inquiry was the Clean Water Act, 2006, known as Bill 43.

Why it matters: Farmland trusts keep productive land affordable and protected against development, creating foodbelt preserves on an individual farm-by-farm basis.

“I’m not against development, but they need to be smart about it,” said the sixth-generation farmer. “In Ontario, we have half of the class one land in all of Canada. It’s mostly in the Golden Horseshoe, which we are here, and it’s being gobbled up faster than you can see.”

Stevens’ farm operation, Wilmot Orchard, is a microclimate that allows for the growth of 11 varieties of blueberries and several varieties of apple trees. The rapid development around their Durham Region area heightened the importance of preserving farmland, and he hopes their participation in the initiative inspires other farmers to consider similar measures.

He also examined the long-term implications of developer pressures on land prices and the ability of young farmers to purchase land, particularly in areas where urban-rural integration had intensified.

“The only way a young farmer in this area is going to be able to buy a piece of land is if it is put into the trust because then it has no development value,” explained the sixth-generation farmer. “Hopefully, other people in the area catch on to this, and maybe someday, there may be another piece of property these young people can afford to buy at farm prices.”

By placing his land in a trust, it will be priced according to the agricultural land value rather than inflated developer prices, where Stevens said landowners are often offered 10 times the value of the land for residential or industrial use.

It also highlights the challenge of succession planning and the need for young people to see the value in farming, said Judi Stevens, Charles’ wife and farm co-founder.

Placing an easement on farmland alone won’t bolster the agriculture sector or make it sustainable, Judi explained; you must cultivate a drive and desire in young people to farm.

“Even if they (older farmers) do put the land into a farmland trust,” she explained, “there has to be enough awareness and enough interest in young people or other people to want to buy a farm.”

As it stands, many farm youths are opting for city careers, leaving farmland and farmers, who are ready to retire, vulnerable to the pull of developer per-acre pricing.

Margaret Walton, chair of Ontario Farmland Trust, is a leading expert in agricultural planning, with over three decades of experience in developing planning policies that support agricultural sectors in areas subject to urban growth pressures.

“Despite the work that we’ve done, it’s quite clear that strong planning policies are not enough,” said Walton. “We need to have other mechanisms for making sure that what we have is protected into the future.”

With the addition of Stevens’ 164 acres, the Ontario Farmland Trust now has 2,700 easement-protected acres provincially, with a goal of reaching 10,000 protected acres by 2029.

“You can’t think about the dollars and cents of it (placing land in trust) because if you do, you probably will never do this,” said Charles. “But as I say, I’ve never seen anybody take even one dollar to their coffin and been able to use it.”

Source: Farmtario.com