Walkerton water crisis ignited collaborative effort to protect water in Ontario

The Walkerton Inquiry resulted in widespread changes to the regulations governing water quality in Ontario.

It brought together governments and land stewards such as farmers in a collaborative effort to keep drinking water safe.

One of the most significant pieces of legislation instituted as a result of the inquiry’s findings was the Clean Water Act, 2006, known as Bill 43. This act created community-based source protection committees, representing a cross-section of sectors and geographic areas within conservation authority boundaries.

“Conservation authorities still have a planning overview role as designated source protection authorities, and they work with the local source protection committees,” said Carl Seider, project manager of the Saugeen, Grey Sauble, Northern Bruce Peninsula Source Protection Region.

Read Also

Boundary Roasting Co. supporting farmer mental health with new coffee

A new partnership between Boundary Roasting Co. and Agriculture Wellness Ontario is offering Ontarians the opportunity to contribute to the…

Seider, a risk management official at the Grey Sauble Conservation Authority, has worked for more than two decades to ensure the area meets and exceeds the Act’s regulations.

Overall, he said the source water protection program has been successful, with good support from the farming community despite contention and concern voiced in the early meetings regarding the program’s implications.

“We have come a long way in terms of educating and getting buy-in from farmers. Now we are able to go out to these farm events,” he said. “We are not seen as a roadblock to the community.”

The committee now meets three times a year to review the Act’s plans and ensure the measures are relevant and effective. It also considers improvements, as well as decides if new wells or changes require incorporation.

The Saugeen, Grey Sauble, Northern Bruce Peninsula source protection region encompasses 38 municipal residential drinking water systems. Of these systems, 29 utilize groundwater sources (aquifers), eight rely on surface water sources, and one combines both groundwater and surface water.

One area of focus is karst areas, a landscape characterized by unique geological features formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks, primarily limestone, by underground water. Found across Grey and Bruce County and in pockets of Eastern Ontario, Seider said these highly vulnerable areas have limited topsoil, which is affected by heavy farm activities.

“We have been working with the local federations and farm community to highlight those threats and where we need to increase our protection above and beyond best practices,” he said, adding that practices are continually evolving.

“They are very vulnerable to any kind of runoff that can get into those cracks.”

He said that most farmers already do good work and require only minor improvements, such as tweaks to timing or record-keeping, to ensure that farm practices won’t contaminate local drinking sources.

“We have consistency in best practices and managing agricultural activities and threats across the province, and [the Act] gave credit to the forward-thinking and progressive farmers and larger operators that, for the most part, were doing all of the best practices already,” explained Seider. “That sort of created a level playing field for everyone else to be in compliance.”

Overall, conservation programs have been successful in ensuring that everyone meets the same standards.

A 2024 report by the protection region found that 44 risk management plans were either renewed or newly established throughout the region, andrisk management inspectors conducted 69 inspections of prohibited or regulated activities, achieving a 100 per cent compliance rate.

The report stated that of the 21 municipalities required to complete an official plan conformity exercise, 20 had been amended and one was in progress. Additionally, septic inspections within vulnerable source protection areas, required once every five years under the Clean Water Act and Building Code Act, were completed.

The report found that in 2024, three septic systems were inspected, including one that required significant maintenance. Subsequently, staff contacted the municipality to ensure that the noted deficiencies have been addressed.

The organization has increased the number of inspections scheduled for 2025 as part of the second round.

Looking to the future, Seider believes that continued efforts will be necessary to protect vulnerable soils and landforms as farming intensifies. He noted that areas such as Grey-Bruce have traditionally served as grazing lands.

“If they become intensive, then that’s an area we want to make sure we have good information and work with those landowners to understand the sensitivities,” he said, adding that conservation areas are starting to see the intensification shift north as farmers look for arable land that is more affordable than southern regions.

“Some practices that might be suitable in the south are moving north, where they haven’t been as common.”

Conservation areas are working to address potential issues through outreach and awareness programs, providing information to farmers engaged in more intensive production levels, said Seider.

“Other non-municipal or private systems could still be vulnerable to contaminants even though there are similar setbacks,” he said. “It is a big role to educate people moving into these areas and understanding the nature of having your own well, your own septic – things you have to maintain as you become your own municipal operator and understanding the broader impacts between neighbours is a challenge.”

Seider said he and his team have been working with municipalities and realtors so new residents have a clear understanding of what living on a property with a private well entails.

“We have lots of great material for people living on these properties and all the best practices that go into these activities,” he said. “We become a go-between for sharing that information.”

Maintaining government support

Seider notes that accessing funding to ensure best practices are met remains a challenge for organizations like conservation authorities.

“It’s a balance because our program is entirely funded by the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks so in terms of source protection plans and maintaining of those plans we are reliant on their funding,” he said, adding the last provincial agreement was three years, indicating a desire for long term support.

“We want to keep them aware that any cuts would have impacts on the ground.”

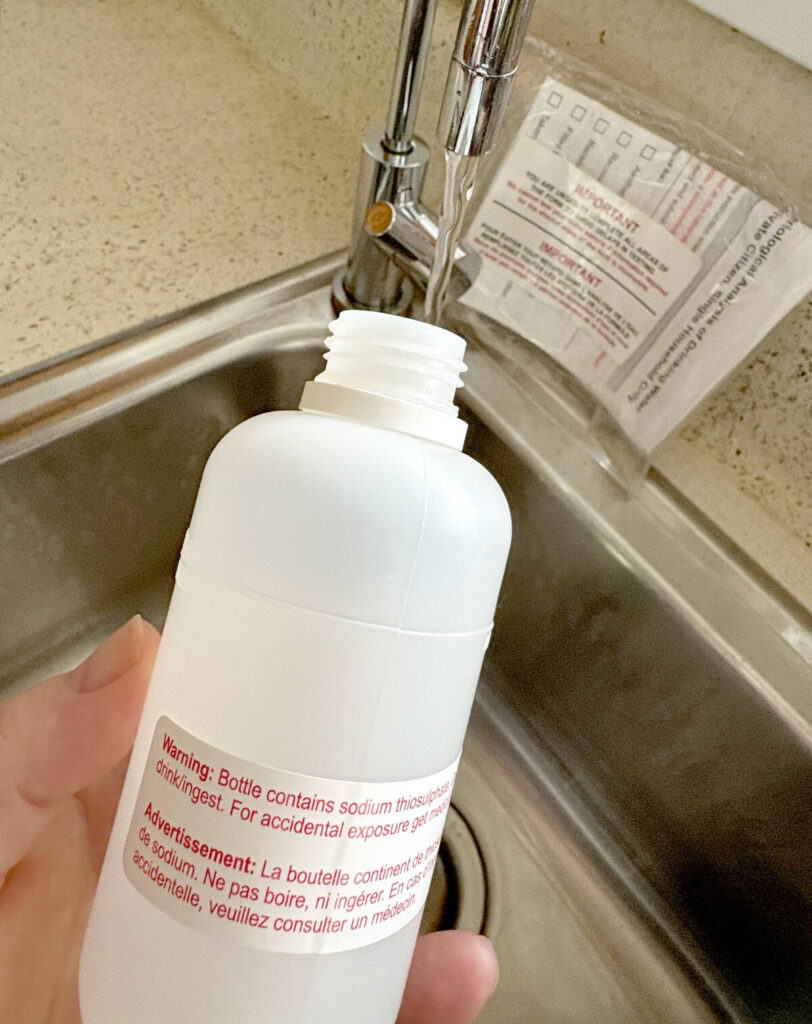

Even with active funding, advocating for long-term funding maintenance is necessary. Seider points to a recent threat by the ministry to reduce the number of private drinking water samples and labs that would receive funding.

His organization and others wrote to the minister urging continued funding, receiving a response months later confirming that services would be maintained.

“If we get information or we feel there is potential changes that would change our level of protection, then obviously we would speak up and use our partners to speak up.”

Local conservation authorities lack strong connections with the federal government but have developed significant outreach to First Nation communities. Seider highlighted recent municipal service upgrades in the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation region, located north of Wiarton on the Bruce Peninsula, adding that they regularly attend source water protection meetings.

The area, which has been under a boil water advisory since January 2019, is completing the building of a new water treatment plant and upgrading the current water distribution system.

“We like to share information with them in terms of source water protection for their implementation,” he said.

Seider said that these and other program successes boil down to funding. Since the initial implementation of the Clean Water Act, funding has decreased. Despite constrained budgets, he argued that the focus should remain on protecting high-risk areas and establishing a priority system.

Early funding provided upgrades to septic systems, which increased buy-in and support from the local farm community, Seider explained, but it’s been years since those funds were available. Now, there are new owners and threats to address that could benefit from similar implementation and stewardship.

“We are always pushing for more stewardship funding,” he said. “We had great success when the province was getting money to implement the source protection plans, giving money to farmers, landowners to fence cattle out of streams.”

Source: Farmtario.com