Climatolgists ring drought alarm | The Western Producer

Farmers should not underestimate the drought of 2021, says a North Dakota climatologist.

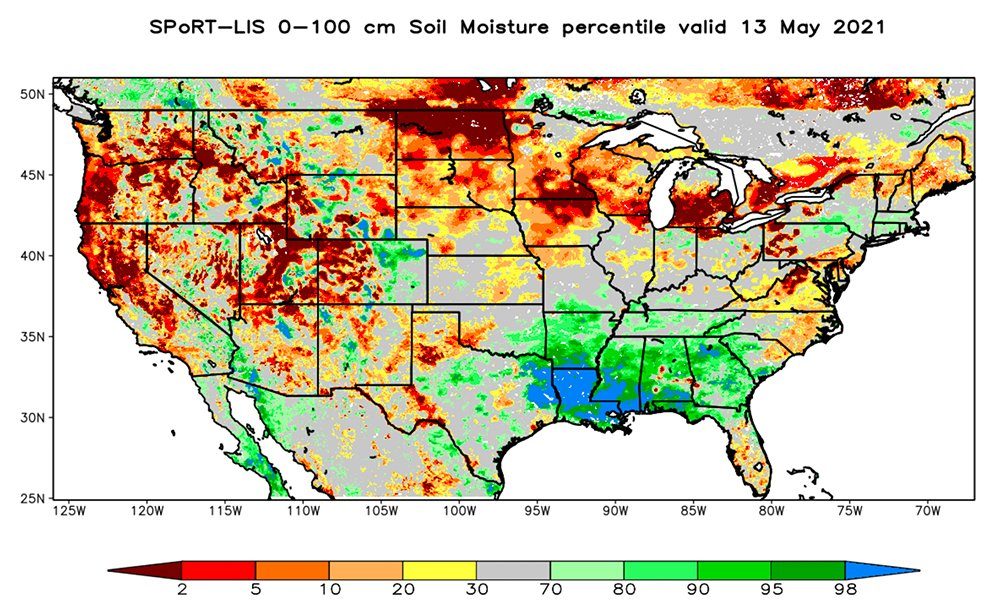

Data from NASA shows that millions of acres of farmland, in northern North Dakota and across the border into Manitoba and Saskatchewan, have extremely low soil moisture this spring. As of the middle of May, NASA rates the soil moisture in the region at the one to two percentile — for soil that is zero to 100 centimetres deep.

This spring, soil moisture in the region could be at its lowest level on record.

“If I was looking at the soil moisture for 100 years and rank it from driest to wettest, the current conditions right now would lie between one and two (for driest),” said Adnan Akyuz, North Dakota state climatologist.

As of the middle of May, 85 percent of North Dakota is in extreme drought, he added.

“The dryness is unprecedented, right now…. It is the driest nine-month period on record, since 1895.”

The drought, though, is broader than a lack of rain last fall and minimal snowfall this winter. Many parts of

Manitoba, Saskatchewan and North Dakota have received less than normal precipitation for nearly two years. That’s why soils, at depth, are abnormally dry.

Akyuz relied on NASA data, from the Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center, to reach his conclusion that it’s the first or second driest spring in 100 years.

Canadian data tells a similar story.

“I don’t know the exact ranking I would provide, but it’s in that range,” said Trevor Hadwen, agro-climate specialist at Agriculture Canada in Regina and part of the team that manages the Canadian Drought Monitor.

“I’m not sure it’s the driest ever… we’re showing it’s in the 95 percentile…. Out of 100 years, it’s one of the top-five driest years.”

Looking across North Dakota, it’s hard to exaggerate the severity of the drought, Akyuz said.

The United States Department of Agriculture North Dakota crop progress report for May 10, shows subsoil moisture supply is rated at 52 percent very short and 29 percent short.

In Saskatchewan, soil moisture is also poor. As of May 10, based on the provincial crop report, it was a 45 percent short and 23 percent very short on cropland. For forage land, it was 45 percent short and 32 percent very short.

Since last summer, minimal precipitation has fallen on the region. Weyburn, Sask., for instance, received only 50 millimetres of rain and snow from Sept. 1 until the end of March. Normal for the period is 150 mm.

It will take many rains this summer to replenish the soil moisture, which means a fundamental shift from dry to wet weather.

“It is going to take above normal precipitation (for) several months,” Akyuz said.

Hadwen agreed that there isn’t a short-term fix to the problem.

In April, a snowfall across much of the Eastern Prairies produced about 25 mm of moisture. That wasn’t nearly enough to change the situation.

“We looked at that with the Drought Monitor and decided, nope, that amount of moisture didn’t solve anything,” Hadwen said. “We didn’t (change) the drought classification even though we got an inch of moisture.”

In the top layer of soil, there is more moisture and seeds will likely germinate in the drought-affected region. But the shortage of moisture in the subsoil is troubling. It will require timely rains, perhaps once every 10 days, to get crops through the growing season.

“(Then) you’re probably going to be fine,” Hadwen said. “(However) I’m not sure we’ve ever had (that).”

The U.S. Climate Prediction Centre is forecasting a warmer than usual June, July and August for the northern plains. That means any rain that does fall, is more likely to evaporate.

Contact robert.arnason@producer.com