Financial stress, what’s the hold-up?

By Steven Kaszab

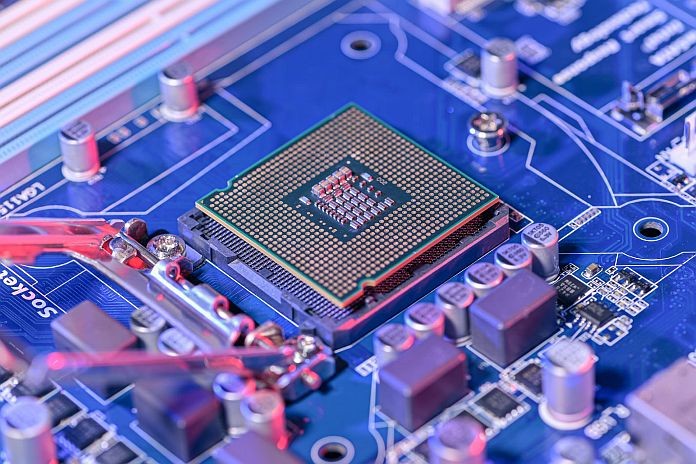

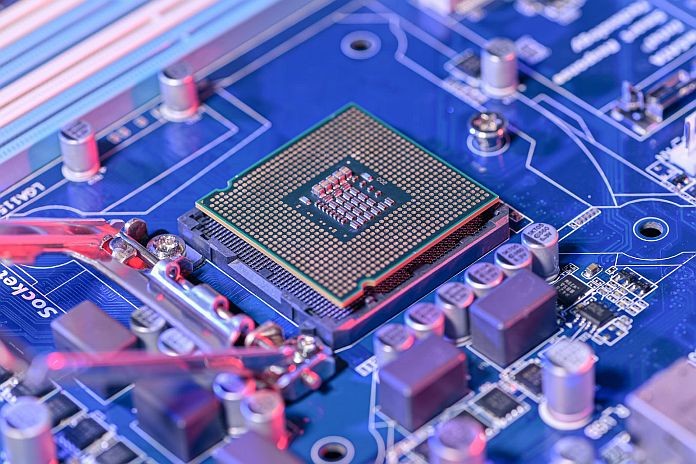

For much of this year, our next financial survival was locked in a zero-sum competition with people eager to upgrade their machinery. Many firms are struggling to receive their machinery and high tech ordered long ago but not shipped to them as of yet due to a shortage of microchips.

Around the world, many of the largest industries are jockeying to secure scarce stocks of computer chips. Automakers have slashed production for a lack of chips, threatening jobs from Japan to Germany to Canada and the United States. Apple has cut back on making iPads. Retailers have prepared for a holiday shopping season pockmarked by shortages of must-have electronics.

Companies that make computer chips — most of them clustered in Asia — have now ramped up production while scrambling to fill orders from their largest customers. That has made purchasing chips exceedingly difficult for smaller companies. Niche buyers are medical suppliers and tech firms that produce life-saving machinery for hospitals.

‘Medical devices are getting starved everywhere. The question now is do we need one more cellphone? One more electric car? One more cloud-connected refrigerator? Or do we need one more ventilator that gives the gift of breath to somebody?’

Manufacturers are beseeching their suppliers to allocate more of their goods so that companies can work through a growing backlog of orders.

This campaign has yet to yield more chips, though it has provided poignant lessons about the priorities at work as the global economy strains to return to normal nearly two years into the pandemic.

Industry is fighting against very big-name automotive companies, cellular communications companies and others who also want more supply. Small business is a small percentage of the total semiconductor chip output that we don’t often get the attention.

The shortages are in large part the result of botched efforts to anticipate the economic impact of the pandemic, along with some conspiracy policies coming out of China. Seems the word is Chinese industry producing these chips has a large array of this product held under lock and key, waiting for governmental permission to release them slowly and most profitably.

As COVID-19 emerged from China in early 2020, it sowed fears of a global recession that would destroy demand for a vast range of products. That prompted major buyers of chips — especially automakers — to slash their orders. In response, semiconductor plants reduced their production to stock levels. That proved a colossal mistake. The pandemic shut down restaurants, movie theatres and hotels while slashing demand for cars.

But lockdowns imposed to choke off the virus increased demand for an array of products that use chips, like desktop monitors and printers for newly outfitted home offices. By the time global industry figured out that demand for chips was surging, it was too late. Adding chip-making capacity requires as much as two years of lead time and billions of dollars.

In North America, Europe and elsewhere, medical device manufacturers are governed by strict product safety standards that limit their flexibility in adapting to trouble. Once a company gains regulatory clearance to use a supplier, it cannot simply seek out a new one that might have a ready stock of chips without first going through a time-consuming approval process.

Far from simple components, computer chips come in enormous varieties, each made with multiple parts that are typically made in multiple countries.

It has been said that while other Asian Manufacturers stopped stocking parts for fear of the market low barrel, China built its stock intending to steal market share worldwide once the market opened in a massive fashion. It’s so unfortunate how money controls everything, and that business priorities are skewed.

What have we learnt here? Like so many other items presently built elsewhere and imported into our homeland, we need to manufacture these products here, and supply our product to our national and global markets.

Source: caribbeannewsglobal.com