Getting creative with income streams at Jack Miner Bird Sanctuary

Limited resources are a perennial problem for conservation organizations. At the Jack Miner Migratory Bird Sanctuary, a non-profit conservation park in Essex County, staff and volunteers are trying to diversify income streams in an effort to improve the area’s ecology, and help people better connect with the natural landscape.

Read Also

Farm business cybersecurity an ongoing concern

Cybersecurity is a best practice in farm business risk management, but requires collaborative support to be successful and accessible. “(Our…

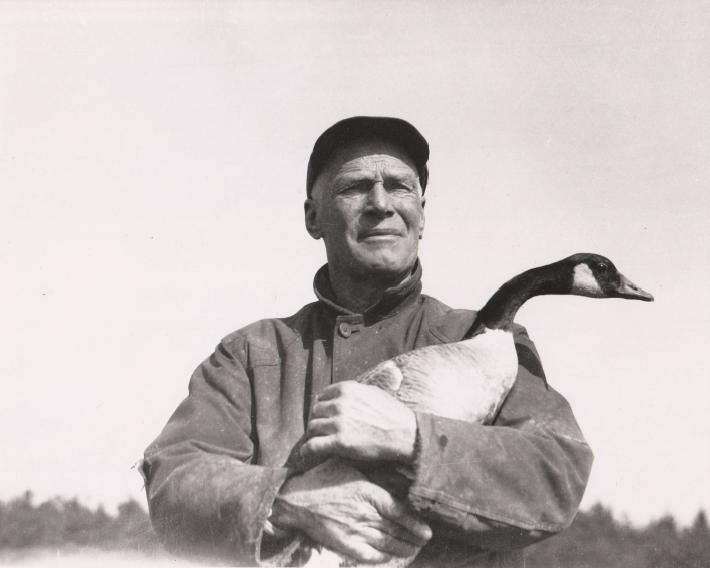

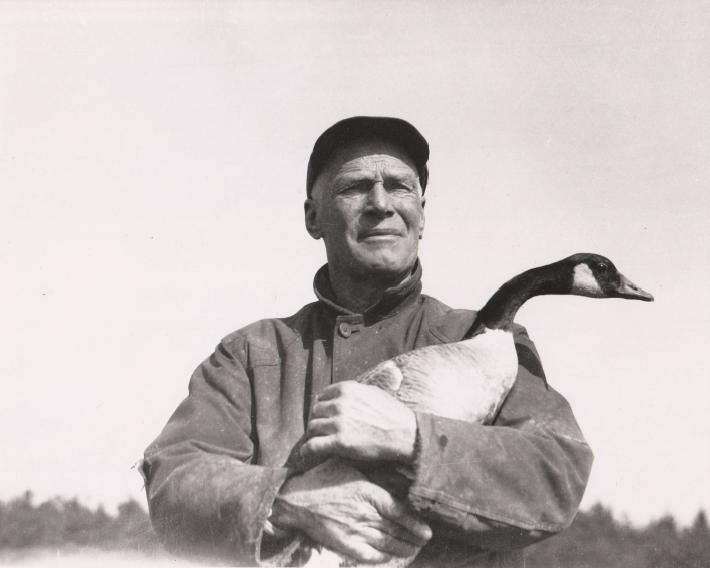

Jack Miner Migratory Bird Sanctuary was established in 1904 by its namesake, Jack Miner – an internationally famous naturalist and communicator considered by many to be the founding father of the North American conservation movement.

At a time when wild species conservation was non-existent, Miner’s intent was threefold: to provide space for geese, ducks, and other waterfowl as they traversed north-south migration routes, provide opportunities for scientific study of wild avian species, as well as educational opportunities for the public. Bird banding – a practiced used worldwide in avian research and management projects – was first devised and employed by Miner at his sanctuary, and continues to be part of its core mission. Over 100,000 birds have been banded at the Sanctuary in the last 120 years.

The Sanctuary was an enormously popular tourist destination in the early decades of the twentieth century. Miner’s work also brought him recognition from political leaders like Canadian Prime Minister McKenzie King and King George VI, industrialists like Henry Ford, famous athletes and many other notable individuals of the era.

Bird banding, and the possibility of participating in the process, still attracts visitors. So do the grounds – some 420 acres divided between working agricultural fields, woodlands and walking trails, ponds, as well as a museum and educational facilities. Conservation-focused education programs also attract families and school groups from across the region.

Managing thin resources

As a non-profit, however, resources to keep the place going are not necessarily consistent or abundant.

Matt Olewski is the Sanctuary’s director of education and community engagement. He’s one of three full time staff supported by a part-time employee, board of directors, and what he calls “an army” of volunteers. But there’s a lot of grass to cut, trail to clear, programing to develop, ponds to maintain, funding applications to fill, and a myriad of other jobs which make short work of both staff and volunteer time. Indeed, coordinating volunteers to get work done is itself a significant commitment.

The Sanctuary’s budget comes from donations and revenues raised from its properties (farmland rents, for example). Olewski says he and his colleagues have been trying to stretch available dollars by doing more with the assets already at their disposal, and in a way which could support reinvestment in the Sanctuary. An example was the recent repurposing of an unused outbuilding into an educational facility, to support ecology programming for school groups and families. Educational information and historical artifacts are also abundant, thanks to community support and a wealth of items, from Miner’s time, still in storage.

photo:

Jack Miner Bird Sanctuary

An example of successful partnerships can be seen in the creation of a new wetland augmenting the wider walking trail network. As of this writing, a 14-acre pond complex is currently being excavated with support from Ducks Unlimited and the Essex Region Conservation Authority. Olewski says this represents what’s possible when successful funding relationships are found.

More funding is always needed, though. A lack of time and financial resources has caused some initiatives to stall, including what Olewski calls a “half-finished” viewing pond currently more reminiscent of a golf course water-obstacle than a naturalized area for waterfowl.

“That last phase of naturalizing the pond, we never secured funding for it. It’s another expensive and labour-intensive process to naturalize a pond of that size,” he says. “We’ve been on the hunt for the right funding partner to complete that last phase of the project. Until then, we’re stuck with a beautiful pond that doesn’t have a means of natural filtration.”

More broadly, Olewski and his colleagues would like to transform the Sanctuary’s isolated ponds into a connected, “continuous flow” network. Currently, a number of ponds require annual draining to remove water which, thanks to the volume of waterfowl visiting the area, has become over polluted and sludgy from excessive organic matter. Should a continuous flow system be established, Olewski says, he and his colleagues would realize significant time and expense savings, while improving the Sanctuary’s ecosystem more broadly.

photo:

Matt McIntosh

New income streams

Olewski and his colleagues are also pursuing other, more creative means of expanding the Sanctuary’s on-site income opportunity. This includes a now three-year-old, eight-acre native grassland restoration project which will serve as an ecologically-oriented outdoor wedding venue.

Perhaps a more unique idea is the potential conversion of another eight-acre area into a natural burial ground. Three potential host sites have been identified within the Sanctuary, and pre-consultation for rezoning one of those sites has already been completed. Olewski says they are now determining the best way to move the project forward by, among other means, assessing what environmental assessments will be required.

Though the final decision whether to go through with the natural burial project has not been made, the potential returns are enticing.

“As long as we push the project hard, we will be at capacity in 20 years,” he says, adding their “very conservative” profit projections show the site would net the Sanctuary approximately $2.5 million, assuming 250 plots per acre. It’s possible that amount could be as high as $7.5 million – serious money for a non-profit conservation organization.

“We’re at the point were we’re still exploring the feasibility of it and whether it’s a route we want to take…We’re also working with area funeral homes to see if they are interested. If you don’t have partnership with local funeral homes, it can be incredibly difficult to be successful,” Olewski says.

“The funeral homes in the region all desire the marketing of a natural burial option for their clientele, and currently they don’t have one. If we were approved today and went completely 100 per cent natural burial, we would be the first full-fledged natural burial site in Ontario.”

Knowledge fosters appreciation

Jack Miner had little formal education. Despite this, a lifetime observing the natural world made him an authority in conservation at a time when few worried about ecological decline. Ongoing efforts to maintain and improve his Migratory Bird Sanctuary are, for Olewski, an extension of Miner’s appreciation for the natural world, and passion for conservation education.

photo:

Jack Miner Bird Sanctuary

“Jack stood for more than the Canada goose,” Olewski says. “He created one of the first waterfowl sanctuaries in North America, and was connecting dots on negative human impact and wildlife even before scientists were calling out some of these problems. It doesn’t take an ecologist or doctorate in biology to make those connections. It just takes a person willing to immerse themselves in a natural setting and be hyper aware, and observant.”

“Nobody is going to care about what they do not understand. By better understanding nature we’re encouraging people young and old to be naturalists and conservationists.”

Source: Farmtario.com