Gravity’s heavy pull on trade

WINNIPEG — In 1665 or 1666, Isaac Newton watched an apple fall from a tree and invented the concept of gravity.

About 300 years later, in the 1960s, a Dutch economist named Jan Tinbergen came up with a different concept about gravity.

Follow all our tariff coverage here

Read Also

Canadian beef exporters escape tariff damage

I could almost hear the huge sighs of relief coming from Canadian livestock and meat producers on April 2 when U.S. president Donald Trump announced he was imposing a new 10 per cent tariff on all imports.

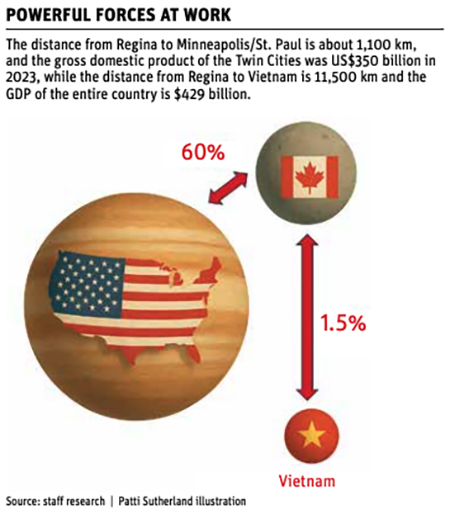

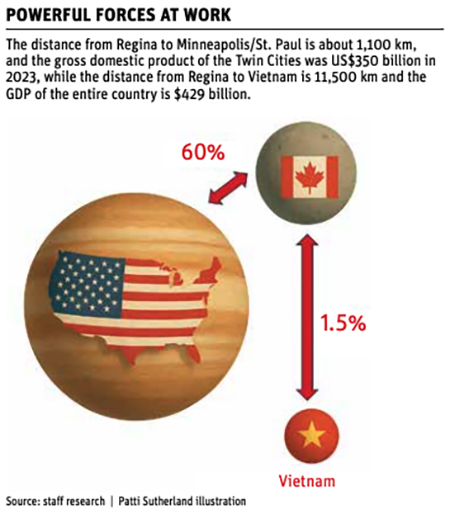

He received the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1969 for his Gravity Model of Trade, which is still considered highly useful for economists. The model explains why 60 per cent of Canada’s total agriculture and agri-food exports are shipped to the United States.

“Basically, it takes Newton’s law of gravity and applies it to trade flows between countries,” said Ryan Cardwell, an agricultural economist at the University of Manitoba.

Newton’s law says the force of attraction between a planet such as Earth and another object, such as the moon, depends on the size of the objects and the distance between the two.

A similar rule applies to trade.

“The larger the size of the economies of two countries, the more they will trade,” says the Tinbergen Institute website.

”The further the distance— physical as well as economic— between these two countries, the less they trade.”

This all seems obvious, but the Gravity Model of Trade is extremely good at explaining trade flows between countries.

It’s also an important model to understand at this moment, given the trade and tariff chaos of 2025.

U.S. president Donald Trump has imposed tariffs or threatened additional tariffs on Canadian goods a number of times in the last three months. Trump’s rhetoric and actions have provoked strong reactions on this side of the border.

“The old relationship we had with the United States … is over,” Liberal leader Mark Carney said in late March.

“We will need to ensure that Canada can succeed in a drastically different world.”

Carney isn’t alone.

Dozens of politicians and media pundits have said that Canada should reduce trade with the United States and divert exports to other nations.

That’s easy to say, but difficult to do.

America is an economic powerhouse, and 75 per cent of Canadians live 200 kilometres from the U.S. border.

A similar culture also contributes to the Gravity Model, amplifying trade flows between Canada and the U.S., Cardwell said.

Getting away from that gravitational pull and shifting trade to a country like Vietnam is difficult.

“When I hear people, especially politicians, saying, ‘we’ need to diversify, ‘we’ need to do this’ … OK, fine, but you’re not the ones making the business decisions,” Cardwell said.

“It’s not like Mark Carney is out there signing hog contracts…. It’s all talk, and it doesn’t mean much, in my view.”

Businesspeople and salespeople are the ones who make deals with companies in other countries. Those sales are much, much easier if the country is close to Canada and is very, very wealthy.

Say, for instance, there’s a Saskatchewan business that produces pea flour and other pulse flours in Regina. The distance to Minneapolis/St. Paul is about 1,100 km, and the gross domestic product of the Twin Cities was US$350 billion in 2023.

In comparison:

- The distance from Regina to Vietnam is 11,500 km.

- The GDP of Vietnam is $429 billion.

One metropolitan region in the U.S. has an economy that’s similar in size to an entire country.

Minneapolis is also home to Cargill and General Mills, two of the largest ingredient and food companies in the world.

As well, a salesperson from Regina can make social connections with a potential customer by talking about winter weather, the Minnesota Vikings and their favourite place to vacation in Florida.

The data shows that gravity, or something like it, is pulling Canadian trade toward the U.S. In the last 25 years, agriculture and agri-food exports to the U.S. have quadrupled, going from $10 billion to $40 billion.

“It’s remarkably high for a reason,” Cardwell said.

Tariffs do affect the model because barriers to trade cause friction and reduce profit opportunities. Some agricultural products might go to other markets because of tariff barriers.

However, even with tariffs, the American market will exert a massive gravitational pull on Canada.

“The last couple of months have been disconcerting,” said Michael Harvey, executive director of the Canadian Agri-Food Trade Alliance.

“But the realities of geography and of access to the world’s greatest market means we’re going to have to work through this situation.”

Contact robert.arnason@producer.com

Source: www.producer.com