Healthy food: This is how your brain decides on a snack

- When it comes to picking a snack, taste has a hidden advantage over healthfulness in the brain’s decision-making process, a new study shows.

- It’s predicted that our brain processes taste information first, before perceived health and this can affect our overall decision making.

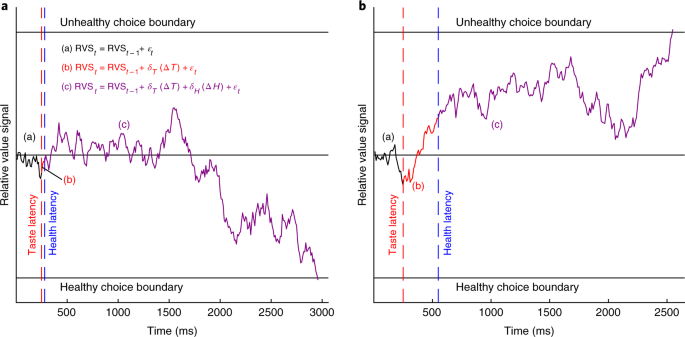

- A recent study showed participants registered taste information in about 400 milliseconds, half the time it takes to registered perceived health benefits.

You dash into a convenience store for a quick snack, spot an apple and reach for a candy bar instead. Poor self-control may not be the only factor behind your choice, new research suggests. That’s because our brains process taste information first, before factoring in health information, the new study indicates.

“We spend billions of dollars every year on diet products, yet most people fail when they attempt to diet,” says coauthor Scott Huettel, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. “Taste seems to have an advantage that sets us up for failure.”

“For many individuals, health information enters the decision process too late (relative to taste information) to drive choices toward the healthier option.”

“We’ve always assumed people make unhealthy choices because that’s their preference or because they aren’t good at self-control,” says study coauthor Nicolette Sullivan. “It turns out it’s not just a matter of self-control. Health is slower for your brain to estimate–it takes longer for you to include that information into the process of choosing between options.”

For the study, Sullivan and Huettel recruited 79 young adults of a median age of 24.4 years and asked them to fast for four hours before the experiment to ensure they arrived hungry.

Participants were asked to rate snack foods on their tastiness, healthfulness and desirability. They were then presented with pairs of foods and asked to choose between them—and the researchers timed their choices. At the end of the experiment, the researchers offered participants one of the foods they had chosen.

Study participants registered taste information early in their decision process—taking about 400 milliseconds on average to incorporate taste information. Participants took twice as long to incorporate information about a snack’s healthfulness into their decisions.

That may not sound like much time. In many cases though, it’s enough to alter the choice we make.

“Not every decision is made quickly—house purchases, going to college—people take time to make those choices,” Huettel says. “But many decisions we make in the world are fast—people reach for something in the grocery store or click on something online.”

The findings could apply to other choices, not just food, the researchers say. For instance, some financial decisions, such as saving and spending choices, may also be affected by how—and when—the brain processes different types of information.

Meanwhile, all is not lost in the war against junk food cravings.

Half of study participants received a blurb before the experiment, stressing the importance of eating healthy. Those participants were less likely to choose an unhealthy snack.

The authors also identified something simple that can help people with their food choices: slowing down the decision-making process. When study participants took longer to consider their options, they tended to pick healthier ones.

“There may be ways to set up environments so people have an easier time making healthy choices,” Huettel says. “You want to make it easy for people to think about the healthfulness of foods, which would help nudge people toward better decisions.”

weforum.org