Here’s what winemakers can teach us about sustainability

- Winemaking is a low-emitting sector – but it’s under particular threat from climate change.

- Many winemakers today are putting sustainability at the heart of what they do, and are increasingly focusing on fair working practices for employees.

- The sector’s efforts demonstrate how collective action and responsibility are key to a sustainable future for businesses elsewhere, too.

There is scarcely a headline today that does not mention ESG, responsible business, or sustainability. The wine industry has an 8,000 year history of adaptation to change, and as such it offers a unique perspective into resilience and lessons that can be broadly applied across sectors and geographies.

To put it in an environmental context, the wine industry is far from the worst emitter. One flight from London to New York city generates almost 1,000kg of CO2 per passenger whereas the average bottle of wine releases just over 1kg of CO2 over its lifetime. So taking just carbon into consideration, that’s almost three years of having a bottle of wine a day to match the emissions of one cross-Atlantic flight. But as recent frosts and fires have shown, even if itself a low emitter, viticulture is threatened by climate change and with it, potentially a substantial part of this over $400 billion dollar global business.

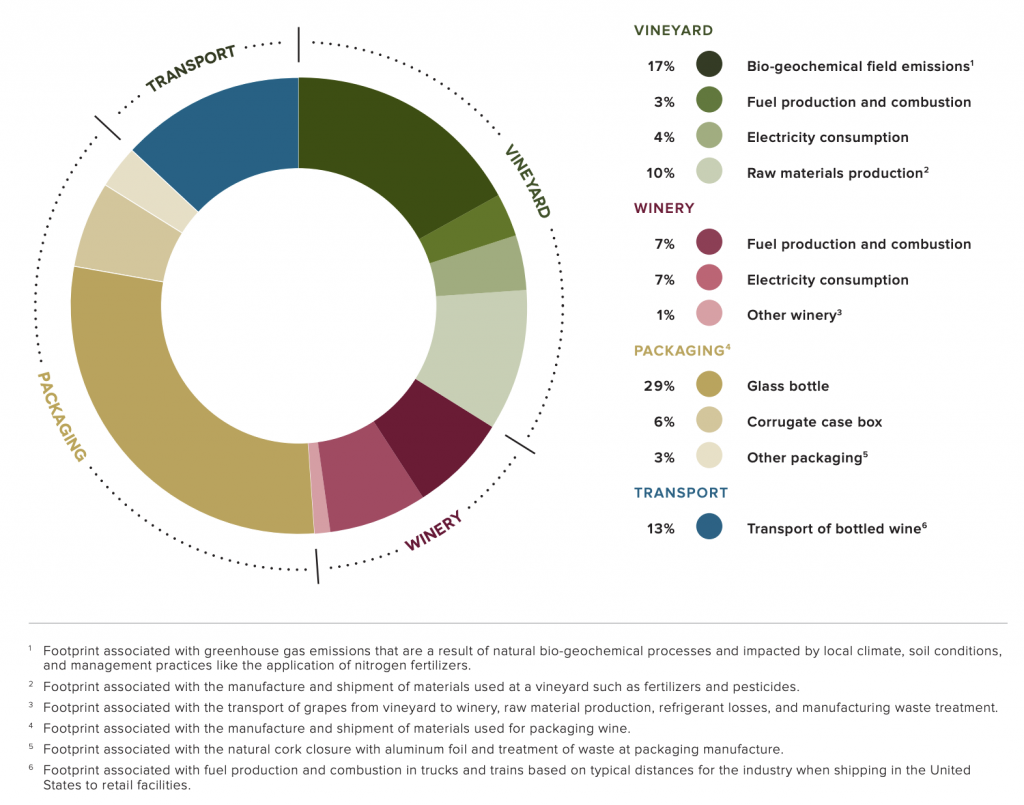

At its core, winemaking is agriculture. Serendipitously, grapes grow best in environments where they need to be stressed to get to nutrients, so they are not as water-intensive as, for instance, almonds. But vineyard activities still contribute around 40% to the carbon footprint of wine. As a response, many farmers today are adopting regenerative agriculture, use of cover crops, renewable energy sources for vehicles, electricity and water, and are leveraging a variety of tools to minimize their impact on the environment. Others are experimenting with alternative rootstock, heat-resistant grape varieties as well as those that take longer to ripen to combat the already very prevalent impacts of climate change.

In addition, most of the carbon footprint of the wine, anywhere from 40-50%, is actually due to the transport and packaging in the glass bottle. The adoption of boxed and canned wine is growing globally, but glass is by far preferred, especially for high-end wines. To add transparency for the consumer, Jancis Robinson, an influential wine writer and critic, is now including bottle weight in her write-ups.

On the social front, winemaking is labour-intensive, especially in regions of the world where the hilly and rocky terrain does not accommodate machinery well. In the summer of 2020, the natural wine world, one where the processes are ostensibly more sustainable and equitable, was rocked by a scandal in which an Italian winemaker was implicated in accusations of abusive labour practices. In today’s world of viral news spread and cancel culture, the winemaker’s business took a huge hit. This incident served to stimulate dialogue on what fair labour practices are, and underlined how interconnected the industry is: a labour issue in a brand that stakes its reputation on being more conscious does not remain a local issue.

In response, some importers have begun requesting labour statistics to be reported, one even using a recognizable nutritional facts label (see below) which highlights the size and nationality of the picking crew, total number of hectares owned and bottles produced, length of harvest and workday, housing and meals provided, as well as farming philosophy.

On the other hand, labour abuse and violations are a global issue (California, Champagne, South Africa) and some point out that material change will only come when the larger mainstream producers begin to make changes. And that is only likely to follow when the mass consumer, not the more niche natural market, demands it.

This is where governance standards can also be of great influence. More and more wineries and industry-adjacent companies are attaining B-Corp status, which attests to business practices beyond the vineyard, from ingredients to supply chain, and re-evaluates companies every three years to ensure that the standards are continuously followed. While a mechanism for signalling a baseline of practices, attaining these certifications can be very resource intensive and not an economically viable option for smaller wineries.

Outside of individual companies’ activities, the Porto Protocol is a not-for-profit platform for the entire viticultural value chain that aims to be a catalyst of change and provide resources and an avenue for collaboration. Its letters of principles call on the industry to commit to making incremental changes and to work collaboratively in the battle against climate change. The IWCA, founded by Familia Torres (a 150 year-old global wine company based in Spain) and Jackson Family Wines (the ninth-largest wine producer in the US) is a collaborative group of wineries committed to carbon reduction and is the first wine organization to have joined the UN’s Race to Zero campaign.

Glass half-full

So why should we take note? And what can we learn from the lessons of the wine industry?

No industry or region can escape the effects of climate change. As winemakers around the globe are increasingly realizing, the cost of insuring their livelihoods is quickly making it unprofitable for insurers to do so. Given the increase in ‘once in a century’ natural disasters, the higher preponderance of these events might make whole regions and industries uninsurable, completely upending the economics of operation.

You cannot improve what you do not measure (and report). From understanding the specifics of emissions and identifying the transport and glass bottle as the main culprits to digging deeper into labour practices, change will not be possible without quantitative analysis and transparent reporting

Technology implementation and innovation are a vital part of the equation. Wine industry leaders are exploring ways to not just adapt to changes via climate-resistant clones, or reduce carbon impact via renewable energy and electric vehicles, but experimenting with becoming a carbon-negative industry via carbon capture.

Most importantly, what the wine industry example demonstrates is that both collective action and collective responsibility are necessary to ensure long term sustainability regardless of industry and its individual impact.

weforum.org