How can smarter farm subsidies drive ecosystem restoration?

- Governments give out $700 billion in agricultural subsidies globally; the goal of this is to boost crop yields and farmer incomes, while also developing rural areas.

- However, this money can inadvertently drive people to clear forests for farmland.

- To reverse land degradation and significantly increase crop yields, governments need to support small farmers.

- A new WRI report, outlined below, highlights the key steps needed in order to achieve this goal.

Every year, governments give out $700 billion in agricultural subsidies globally. Though well-intentioned, these farm subsidies sometimes work against their core goal: boosting crop yields and farmer incomes while developing rural areas.

Farm subsidies can also inadvertently drive people to clear forests to produce commodities like soy and beef, which caused around 20% of global tree cover loss in 2018. This has a major economic toll, too. Deforestation and land degradation lower the productivity of soil in forests and on farms, costing rural communities as much as $6.3 trillion a year. Agriculture, forestry and land use change are also a major source of carbon pollution, representing 18.5% of climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions in 2016.

Governments urgently need to reverse land degradation while significantly increasing crop yields in order to feed 10 billion people by 2050. This year, governments specifically need to protect the food security of the 97 million people that the COVID-19 pandemic pushed into poverty in 2020. Achieving that outcome is only possible if they support the small farmers — working on less than two hectares each — that produce up to 34% of the world’s food supply.

A new WRI report highlights how governments can shift public farm subsidies to stimulate inclusive rural development while protecting the environment and smallholder farmers.

Shifting farm subsidies can help farmers and land restoration

By providing farmers with fertilizers, pesticides and technical support, agricultural subsidies brought millions of people out of poverty during the Green Revolution in the 1950s and 1960s. But today, many programs are encouraging farmers to use an excessive amount of pesticides and fertilizers in the quest for immediate yield improvements, without accounting for how these chemicals can damage the soil and hurt long-term productivity.

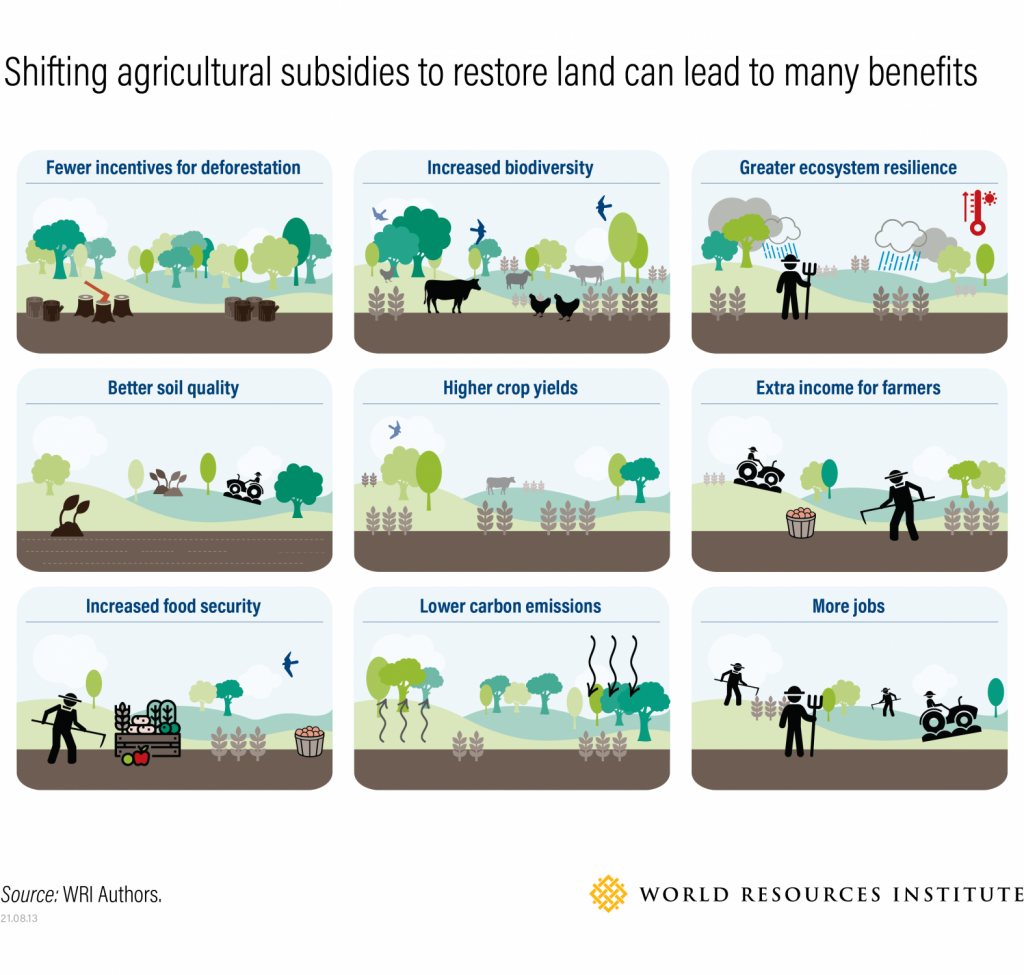

By shifting these underperforming farm subsidies, which have contributed to the degradation of 75% of the Earth’s land, governments can better achieve their goals of helping rural economies. These revamped incentive programs can — without hurting farms’ bottom lines — help farmers restore the health of the land while building climate resilience into local economies.

Investing in land restoration does not mean divesting from agriculture; it means supporting a low-carbon version of farming that can provide sustainable returns for decades. Agroforestry, where farmers add trees to cropland, and silvopasture, where they grow trees on their livestock’s grazing land, are widely adopted techniques in parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America that improve the health and productivity of the land in the long-term.

Revitalizing 150 million hectares of degraded agricultural land with these and other techniques could generate $85 billion in net benefits, provide $30 billion to $40 billion each year in extra income for smallholder farmers and grow additional food for nearly 200 million people.

Restoring landscapes is not a silver bullet to the problems of climate change and rural poverty. But directing public investment to farmers more effectively can help countries meet their long-term food security, rural development and environmental goals. This is important for the post-coronavirus recovery: Government stimulus programs to rescue struggling farmers can’t sacrifice long-term sustainability for short-term economic gains.

Here are four things governments can do to craft successful public land restoration policies:

1. Remove farm subsidies for underperforming fertilizers and pesticides

In 2005, after a period of poor weather and food shortages, the government of Malawi created a subsidy program for farm inputs like fertilizer, spending about 60% of its total agricultural budget. Although the fertilizer the program provided increased maize yields at first, its impact declined over time (while damaging the land with inorganic chemicals that can acidify the soil and make it harder for plants to grow).

Policymakers in Malawi and elsewhere can slowly remove expensive subsidies for harmful fertilizers and pesticides in areas where yields no longer rise as people add these inputs. If these funds can be freed up for new programs that help farmers restore land through agroforestry or silvopasture (in support of its National Forest Landscape Restoration Strategy), they can help build climate-resilient rural economies.

2. Create incentives for land restoration

Governments provide more than $1 million per minute in global farm subsidies, some of which incentivize farmers to clear forests to plant subsidized cash crops. Because farmers aim to maximize their profit (or eke out a living) and government support is a major source of their income, many farmers follow the money and convert biodiverse tropical forests — which store huge amounts of carbon — into sprawling single-crop farms.

Repurposing agricultural subsidies can help farmers follow the money in the opposite direction. Paying them to restore degraded farmland would help create sustainable value chains for forest products and lower the initial cost that landholders shoulder as they wait for the benefits of new trees to take root. This, combined with new mechanisms that compensate farmers for the environmental benefits of their land, can accelerate restoration and generate higher returns.

Shifting farm subsidies is also important because protecting, sustainably managing and restoring forests are the least expensive and most effective nature-based solutions that tropical countries can use to meet their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Climate Agreement.

Some countries are already making the change. In Burkina Faso, forest cover had halved since 2000 due to increasing demand for farmland and cattle pasture. In response, the government initiated a $30 million Forest Investment Program in 2010 that paid people to grow trees on their farms. This scheme not only restored land, it also gave households enough money to spend 12% more on food, reducing food insecurity by 35-60%.

Progress is also underway in Latin America, where farmers paid by Brazil’s Bolsa Floresta and Bolsa Verde programs to protect forests next to farmland have seen higher crop yields, and in Asia, where India’s National Agroforestry Policy has increased the country’s tree cover by 2%, mostly on farms.

3. Put small farmers first

Large landowners and corporations often benefit disproportionately from existing subsidies. Given that farmers with fewer than 15 hectares of land produce most of the world’s food, governments must design incentive programs that reach them as intended. Small farmers also need more clearly defined land rights. Without legal title to their land, they are often ineligible for subsidies.

Farmers both big and small can work together in coalitions to encourage governments to facilitate markets for the ecosystem services, like clean water and carbon sequestration, that restored land produces. When restoration doesn’t pay, it doesn’t happen.

Ghana has applied these lessons. There, wildfires — caused by hunting, slash-and-burn farming and charcoal production — ravage forests and threaten local livelihoods every year. To prevent future fires, officials encouraged small farmers to adopt more sustainable land management practices like plowing post-harvest crop residue into their fields rather than burning it.

To restore damaged land, the government of Ghana created a program in 2015 to pay each farmer GHS 200 ($34) to grow trees, improving soil quality, water availability and local biodiversity. When people saw their neighbors receive their first payments, participation tripled.

Farm subsidies like Ghana’s could also help smallholder farmers adopt the latest technology — like climate-resilient, high-yield seeds — to boost their yields in the short term (as they lay the groundwork for the long-term benefits of restoration).

4. Work together

Officials in national agriculture, environment, rural planning and finance ministries need to work together to achieve common goals. Restoring farmland can support governments’ policy goals on climate, biodiversity and rural development, while saving their budgets. This approach will be essential for a post-coronavirus era when many developing countries may need to implement frugal financial policies.

International cooperation is just as important. The recent Restoration Policy Accelerator, for example, brought together government officials from Chile, Mexico, Peru, Guatemala and El Salvador to build up capacity and political will for restoration incentives within the Latin America-led Initiative 20×20 network. By creating a network where officials could talk confidentially with peers to solve problems, the program is moving sensitive policy work forward.

For example, El Salvador is now designing three new policy instruments to enable local banks to: 1) provide loans for people restoring land by sustainably growing food and commodities, 2) invest in restoring key watersheds and 3) reward farmers that grow trees to prevent floods and landslides.

Peru is assessing how an incentive program for farmers who are restoring their land could reduce their upfront costs, produce a return on investment and potentially boost the country’s restoration economy.

Countries can also learn from each other’s work on tracking the progress of their restoration programs. Investing in monitoring, like El Salvador’s custom and simple-to-understand system, provides the data needed to justify new programs or expand existing ones.

Smart policies for a restored future

Farm subsidies can be a major aid for both farmers and the environment. Redirecting where these agricultural subsidies go could provide food for millions while protecting and restoring the world’s forests and farms.

To meet their climate, biodiversity and sustainable development goals, governments should embrace the power of restorative agriculture. Smarter farm subsidies and incentives can achieve more with less. They can help governments achieve these important policy goals without harming the farmers that are the backbone of rural economies.

weforum.org