How green is your food? Eco-labels can change the way we eat, study shows | Food

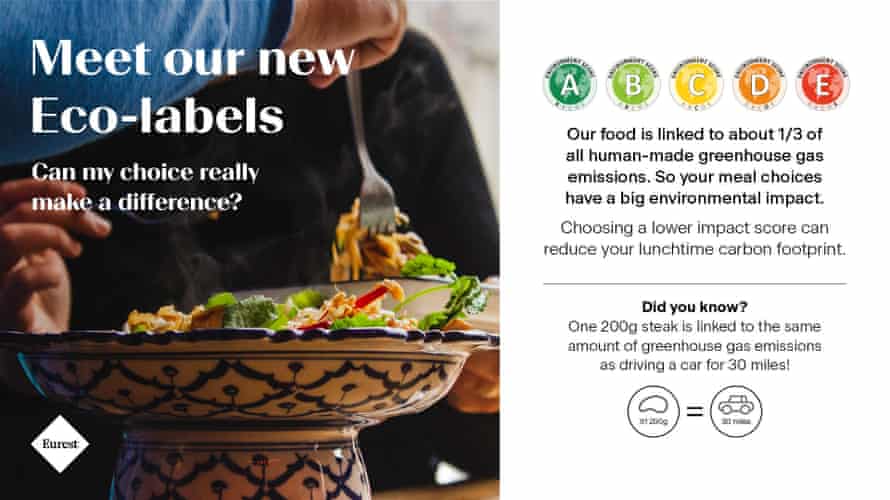

It’s lunchtime at a workplace cafeteria in Birmingham, and employees returning to work after months away during the coronavirus pandemic are noticing something has changed. Next to the sandwiches and hot and cold dishes is a small globe symbol, coloured green, orange or red with a letter in the centre from A to E. “Meet our new eco-labels”, a sign reads.

Researchers at Oxford University have analysed the ingredients in every food item on the menu and given the dishes an environmental impact score, vegetable soup (an A) to the lemon, spring onion, cheese and tuna bagel (an E).

“It probably does help you to start making some choices,” said Natasha King, while eating a plant-based hot meal. She is an employee in the Birmingham headquarters of the UK division of the food services business Compass Group. The company has teamed up with the university for a trial at more than a dozen of its cafeterias across the UK to see if a label can change the way people eat.

Getting people to switch to environmentally sustainable food options through labels is not new: hundreds of food labels exist, from ones that certify organic, to those that promise sustainable fishing. But a new type is gaining steam, one that summarises multiple environmental indicators from greenhouse gas emissions to water use into a single letter indicating the product’s impact.

Some businesses in France began using one this year and the NGO Foundation Earth announced its own trial to begin in UK and EU supermarkets this autumn.

The first challenge for the scientists designing the trial is the image the diners see on the signs. How much information do you include in a label? How do you strike a balance between effective and practical?

During the pandemic, researchers ran studies on an online supermarket where people were given fake money to complete their fake shopping list. The trial gave a sense of what labels were more likely to sway people to buy eco-friendly. They found the most effective way to get people to not buy an item was to use a dark red globe symbol with the word “worse” printed on it. But while effective, it had real world limitations.

“You’re not going to be able to get anyone to use that unless you threaten them with legislation, because they don’t want to say ‘don’t buy this’,” said Brian Cook, the senior researcher at Oxford’s Leap programme leading the project.

And what works for this cafeteria setting, with lots of room for information on walls and beside the food, may not work on food packaging in a supermarket that’s already full of information, much of it government mandated. “The real estate there is highly competitive,” Cook said.

The next challenge in supermarkets is the scale. The sandwiches, soups, and hot dishes laid out in this cafeteria only scratch the surface of the Compass food options. It was the Oxford researcher Michael Clark’s job to go through the hundreds of meals made up of roughly 10 ingredients each, determining the environmental impact. Doing the same for the tens of thousands of products and myriad ingredients in a supermarket would be a Herculean task.

Then the scientists had to create a formula to determine environmental impact – a process full of tough decisions using imperfect data. “There’s neverending ways you can do it and how you weight the different indicators … how you want to nudge people,” Cook said.

This research team decided on four indicators for this trial’s formula: greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity loss, water pollution, and water use (calculated differently based on water scarcity in each region). They weighted each indicator equally in their equation for overall impact.

Other research has looked at land use instead of biodiversity, or using a total of 16 indicators. Whatever the choice, it can change the eco-score that comes out.

“Almonds, you know: great for your health and low in a lot of environment indicators, but then you get to the water, and they are off the charts,” Cook said.

But in most cases, the researchers say the biggest environmental impact will be to get people off meat. “Given that the premise is to get people to shift behaviour, that most correct and scientifically robust approach may actually not be the best approach,” Clark said.

He has considered that a national rollout of labels might need to be based on indicators already prioritised by businesses or mandated by governments, to make the integration as easy as possible for businesses.

In a corner table at the Compass cafeteria, five employees eat together, four of them have chosen a vegetarian meal. They say many of them would usually have opted for meat.

At another table sits Jenny Haines, eating a vegetable stew (rated a C). She does not often think about the environmental impact of the food she eats, but she says it looked appetising, healthy, and was placed right at the front of the hot meals counter.

This was part of an intentional strategy by Compass to find ways to get customers to buy food with a better environmental impact score. Plant-based dishes are placed at the top of menus and at the front of cafe counters, with meat dishes at the back. They do not use the words “vegan” or “plant-based” so people do not feel dictated to, and they gave their dishes a rebrand. “Vegan sweet potato mac n cheese” became “Ultimate New York ‘cheezy’ sweet potato mac”, for example.

At the centre of everything is taste. “Ticking the box isn’t good enough,” said Ryan Holmes, a culinary director at Compass. “We need to put plant-based dishes that can stand next to the meat dishes.”

Some politicians are also interested in this issue. MPs in the UK and Canada have introduced private member’s bills this year aiming to mandate environmental impact labels on food.

Cook gives presentations to business groups and some policymakers in the UK, and says people have a lot of interest in labels. He thinks we will see these labels in some form on products sooner or later.

“It’s definitely part of the toolkit of what you need,” he said. “And in terms of the things that are risky to all stakeholders, this is relatively low risk.”

Source: theguardian.com