The looming rail strike: How did we get here?

The labour dispute between Canada’s railways and the Teamsters Canada Rail Conference (TCRC) reached a critical juncture on August 9.

The Canadian Industrial Relations Board (CIRB) ruled that rail service was not considered an essential service based on the Labour Code’s definition. Following the ruling, both railways issued statements threatening to lock out their employees at one minute past midnight on August 22 in the absence of an agreement.

In a news release, CN begged Labour Minister Steven MacKinnon to invoke Section 107 of the Labour Code, which says that if it is unclear if parties are able to effectively bargain, the minister can intervene.

Read Also

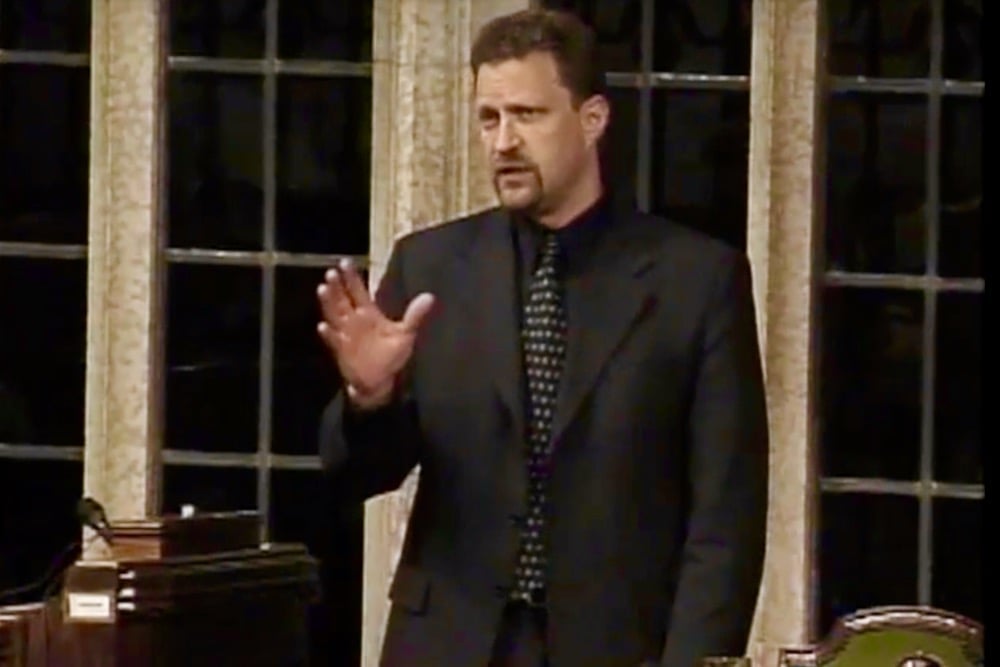

Former federal ag minister Chuck Strahl dies at 67

A memorial service is planned for Aug. 23 in Chilliwack, B.C. for Chuck Strahl, the logger turned politician who served about a year and a half as federal agriculture minister in Stephen Harper’s government, helping carry several of its policy plans through to completion.

In the days since August 9, panic has begun setting in within the agricultural industry. The country has never seen a labour dispute that resulted in a strike or lockout from both of Canada’s rail companies. With harvest ramping up, a suspension of rail services would be disastrous for the industry.

To pressure the minister to follow CN’s advice on Section 107 and impose binding arbitration on the parties, some agricultural groups united in a letter-writing campaign known as “Stop the Strike.” On August 15, MacKinnon sent a letter to the TCRC letting them know that he would not intervene.

And so, the uncertainty in agricultural circles continues.

How did we get here?

The railways and the TCRC have been negotiating since November 2023, and the collective agreement expired in December. The talks stalled over issues including wages, scheduling and fatigue management.

On May 1, the employees of the two railways voted overwhelmingly for strike action, which invoked a 21-day mandatory cooling off period, meaning a strike could happen as soon as May 22.

Then, on May 9, then Labour Minister Seamus O’Regan pumped the brakes and asked the CIRB to rule on whether rail traffic was an essential service. That act put everything on pause.

There were limited negotiations and a few attempts to bridge the gap. Both railways proposed binding arbitration as a resolution later in May, but the union rejected it. An update on the Teamsters website stated, “These carriers are only pushing for binding arbitration to attain concessions that they cannot achieve through collective bargaining.”

In June, the TCRC offered up the possibility of staggered strikes to lessen the impact of work stoppages, which the railways rejected. On their bargaining update page, CN said it only prolongs the risk of extending the strike. “It is like suffering death by a thousand cuts,” read their response.

By the time CIRB released their ruling, the two sides were no closer together.

The CIRB ruling: what does “essential” mean?

Many find it surprising that rail transportation was not deemed an essential service by the CIRB, but the board was ruling on a very narrow definition of ‘essential.’

The authors of the ruling were careful to make that clear. The document acknowledges a railway work stoppage would result in inconvenience and economic hardship, and it might harm Canada’s reputation as a global trading partner.

“While such possible harm is by no means insignificant, these are not factors that are to be considered by the Board when addressing a referral under Section 87.4 of the Labour Code,” it said.

According to the Labour Code, the threshold for essential service is a service that, if stopped, would “pose an immediate and serious danger to the safety or health of the public.” The CIRB said the railways provide no services that meet the threshold.

None of the parties disputed that fact. The railways and the TCRC were in agreement on Section 87.4 of the Labour Code. On February 1, 2024, CN wrote a to TCRC letter saying as much. The excerpt was included in the CIRB ruling.

“With respect to the issue of maintenance of activities pursuant to Section 87.4 of the Code, the company notes that, while its services are essential to both the Canadian and the global economy, it does not dispute your position that these services are not necessary to prevent an immediate and serious danger to the safety or health of the public.”

This is likely why CN and others criticized the government for stalling the process.

In a June 11 release, CN said the uncertainty around the timing of a labour disruption was already hurting CN employees and the Canadian economy at large.

“The Minister of Labour’s request to the Canadian Industrial Relations Board (CIRB) on the issue of essential services is adding to this uncertainty,” the release read.

Greg Northey, Vice President Corporate Affairs with Pulse Canada, echoed that concern.

“When the government asked the CIRB to assess whether that was correct back in May, it just paused everything,” he said. “It took three months for them to come to that conclusion, and now we’re back, back where we started.”

Northey is the spokesperson for the Stop the Strike campaign, and he said the timing couldn’t be worse.

“The repercussions are going to be massive for us because we’re in the middle of harvest,” he said. “One day of outage on one rail line is about a week of recovery. For two rail lines, even if they’re out for three days, we’re looking at weeks of recovery.”

The cooling-off period

The CIRB also had to rule on the 21-day cooling-off period. It was TCRC’s position that a cooling-off period wasn’t necessary and that if there was one, it should only be seven days. The railways were asking for a 30-day cooling-off period so they could prepare for the labour stoppage.

Without a cooling-off period, a strike could have begun as soon as 72 hours after the CIRB released their decision. This would have left little time for the railways to prepare, which the Board felt would “not be conducive to harmonious labour relations.”

The Board ruled that, since there were 13 days left in the 21-day cooling off period when the Minister intervened, that cooling off period would continue after they released their ruling on August 9. That is why the railways set their lockout deadline for August 22.

Where are we heading?

Northey said he was disappointed but not surprised when he heard about MacKinnon’s letter to TCRC in which he declined to intervene in the labour dispute.

“They’re invested in ensuring that there’s a negotiated solution, and obviously it’s a significant move for them to intervene,” he said. “But it is extremely disappointing, because the impacts have already started.”

The railways have begun to wind down shipments, particularly for perishable goods, in anticipation of a lockout on August 22.

Northey said MacKinnon is taking a big risk by refusing to intervene. He said the minister obviously hopes that by not intervening, the parties will feel more pressure and work even harder to come to an agreement. But if he’s wrong, it could spell disaster.

“It’s a billion-dollar gamble,” he said. “No one has the patience for the kind of brinksmanship we’re seeing.”

Source: Farmtario.com