UV light holds grain decontamination potential

Glacier FarmMedia – Tatiana Koutchma foresees a slew of new applications for ultraviolet sanitation, whether it’s helping to keep meat packing lines free of SARS-CoV-2 or knocking fusarium fungus out of grain.

“Before we only had lamps as a source of UV light,” she said. “Now, we have LEDs. They are small, flexible and their lifetime is getting longer, and they’re getting cheaper. So this opens a whole new area.”

Why it matters: Reducing fungal contamination of grains leads to better quality along the production chain, and UV sanitation could offer an effective, low-cost method.

Koutchma is a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC) in Guelph, Ont. She is an expert in the use of ultraviolet light to sanitize everything from food preparation surfaces to food products both liquid and solid and even the air itself in enclosed locations.

One application she and her colleagues are exploring is to use UV to reduce contamination in grain from the fungi Fusarium graminearum, which causes head blight in cereals, and Penicillium verrucosum, which infests stored grain.

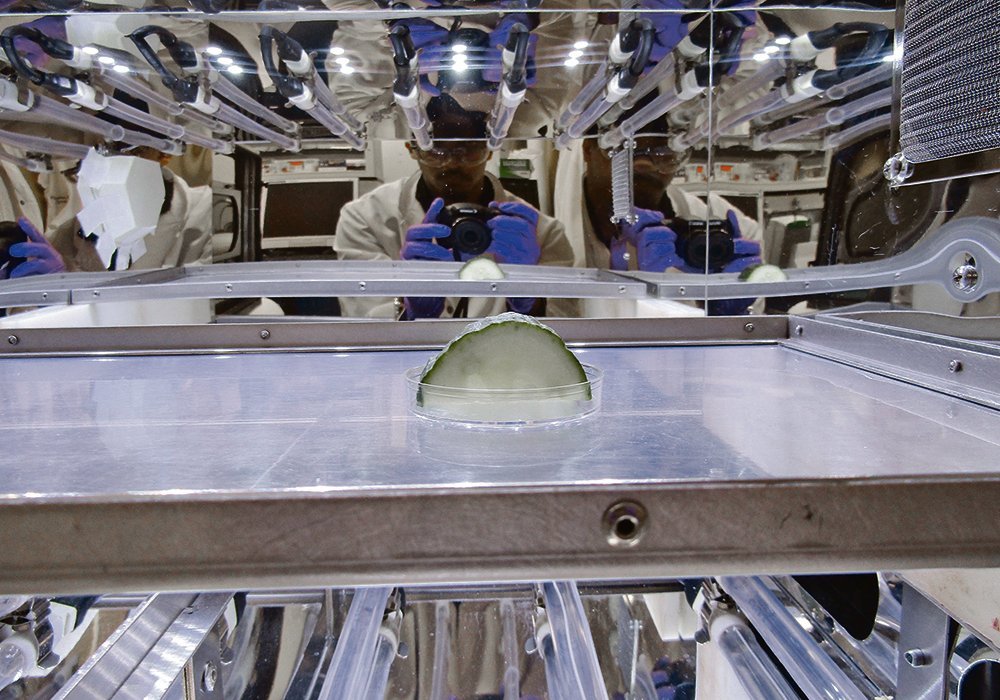

Backed with funding from the Grain Farmers of Ontario and AAFC, the researchers did a proof-of-concept study to see how UV performed. They shone UV light on petri dishes full of fungal spores as well as single layers of fungi-infested wheat and corn kernels.

They found the treatment reduced fungi by up to 99 per cent in the petri dishes and by more than 94 per cent on the grain kernels. The researchers also used UV light on the toxins produced by the fungi, and found they were able to reduce levels by 75 to more than 97 per cent.

The researchers’ findings were published in 2018 in the journal Mycotoxin Research.

UV does its sanitizing work by breaking apart DNA molecules in the fungi so it can’t reproduce. It can be tuned to deactivate mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol, or DON, produced by fusarium. Again, the light breaks the DON molecule. Koutchma said more research is needed to ensure the broken pieces are not harmful as well.

It’s a long way from the lab to the field, but Koutchma and her colleagues are proceeding with the next steps.

“Now we’re in the second phase, trying to develop a pilot scale unit,” she said, explaining the project has been slowed by challenges with funding and service disruptions during the pandemic.

While the lab work confirmed UV light will decontaminate grain when it’s stationary and in a thin layer, this next stage will test it under conditions closer to the real world.

“This is what we are trying to validate right now,” she said. “We’re trying to put it on a conveyor. The conveyor will move the grain and during this movement, the grain will be exposed to UV light.”

The researchers intend to test several types of standard UV bulbs as well as UV LEDs. In the high-volume, high-impact environments of a pedigreed seed plant or production grain-handling system, these offer intriguing possibilities.

Tough, flexible and inexpensive, Koutchma envisions them installed inside systems that shake the grain as it passes through to expose it to the UV light.

“We’re working with a few companies to make these custom units, to play with different sources, with different wavelengths to see which ones work better,” she said. “Maybe we could choose a set of wavelengths for mycotoxins and longer wavelengths for fusarium. It’s the way I am thinking.”

While the UV treatment doesn’t eliminate fungi or the toxins they produce, it can dramatically reduce them. This means safer work environments for farmers and other workers exposed to grain dust, and better quality grain along the production chain from pedigreed seed operations to production farms and end users.

It’s difficult to put a price tag on UV technology for bulk grain sanitation because it’s still being developed, but it is in common use in other industries, particularly food processing. As an example, Koutchma said bulk UV sanitation units for treating fruit juices in commercial production run from $20,000 to $80,000.

“I don’t envision that for grain it would be more than that,” she said. “It may be in this range or less.”

Michael Robin is a reporter for The Western Producer.

Source: Farmtario.com